Brown dwarf

Brown dwarfs are sub-stellar objects which are too low in mass to sustain stable hydrogen fusion. Their mass is below that necessary to maintain hydrogen-burning nuclear fusion reactions in their cores, as do stars on the main sequence, but which have fully convective surfaces and interiors, with no chemical differentiation by depth. Brown dwarfs occupy the mass range between that of large gas giant planets and the lowest mass stars; this upper limit is between 75[1] and 80 Jupiter masses ( ). Currently there is some debate as to what criterion to use to define the separation between a brown dwarf from a giant planet at very low brown dwarf masses (~13

). Currently there is some debate as to what criterion to use to define the separation between a brown dwarf from a giant planet at very low brown dwarf masses (~13  ), and whether brown dwarfs are required to have experienced fusion at some point in their history. In any event, brown dwarfs heavier than 13

), and whether brown dwarfs are required to have experienced fusion at some point in their history. In any event, brown dwarfs heavier than 13  do fuse deuterium and those above ~65

do fuse deuterium and those above ~65  also fuse lithium. Some planets are known to orbit brown dwarfs: 2M1207b, MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb, and 2MASS J044144.

also fuse lithium. Some planets are known to orbit brown dwarfs: 2M1207b, MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb, and 2MASS J044144.

Contents |

History

Brown dwarfs, a term coined by Jill Tarter in 1975, were originally called black dwarfs, a classification for dark substellar objects floating freely in space which were too low in mass to sustain stable hydrogen fusion (the term black dwarf currently refers to a white dwarf that has cooled down so that it no longer emits significant heat or visible light). Alternative names have been proposed, including planetar and substar.

Early theories concerning the nature of the lowest mass stars and the hydrogen burning limit suggested that objects with a mass less than 0.07 solar masses for Population I objects or objects with a mass less than 0.09 solar masses for Population II objects would never go through normal stellar evolution and would become a completely degenerate star (Kumar 1963). The role of deuterium-burning down to 0.012 solar masses and the impact of dust formation in the cool outer atmospheres of brown dwarfs was understood by the late eighties. They would however be hard to find in the sky, as they would emit almost no light. Their strongest emissions would be in the infrared (IR) spectrum, and ground-based IR detectors were too imprecise at that time to readily identify any brown dwarfs.

Since those earlier times, numerous searches involving various methods have been conducted to find these objects. Some of those methods included multi-color imaging surveys around field stars, imaging surveys for faint companions to main sequence dwarfs and white dwarfs, surveys of young star clusters and radial velocity monitoring for close companions.

For many years, efforts to discover brown dwarfs were frustrating and searches to find them seemed fruitless. In 1988, however, University of California, Los Angeles professors Eric Becklin and Ben Zuckerman identified a faint companion to GD 165 in an infrared search of white dwarfs. The spectrum of GD 165B was very red and enigmatic, showing none of the features expected of a low-mass red dwarf star. It became clear that GD 165B would need to be classified as a much cooler object than the latest M dwarfs then known. GD 165B remained unique for almost a decade until the advent of the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS) when Davy Kirkpatrick, out of the California Institute of Technology, and others discovered many objects with similar colors and spectral features.

Today, GD 165B is recognized as the prototype of a class of objects now called "L dwarfs". While the discovery of the coolest dwarf was highly significant at the time, it was debated whether GD 165B would be classified as a brown dwarf or simply a very low mass star, since observationally, it is very difficult to distinguish between the two.

Interestingly, soon after the discovery of GD 165B other brown dwarf candidates were reported. Most failed to live up to their candidacy however, and with further checks for substellar nature, such as the lithium test, many turned out to be stellar objects and not true brown dwarfs. When still young, up to a billion years (a gigayear) old, brown dwarfs can have temperatures and luminosities similar to some stars, so other distinguishing characteristics are necessary, such as the presence of lithium. Stars will burn lithium in a little over 100 Myr, at most, while most brown dwarfs will never acquire high enough core temperatures to do so. Thus, the detection of lithium in the atmosphere of a candidate object ensures its status as a brown dwarf.

In 1995 the study of brown dwarfs changed dramatically with the discovery of three incontrovertible substellar objects, some of which were identified by the presence of the 670.8 nm lithium line. The most notable of these objects was Gliese 229B which was found to have a temperature and luminosity well below the stellar range. Remarkably, its near-infrared spectrum clearly exhibited a methane absorption band at 2 micrometres, a feature that had previously only been observed in gas giant atmospheres and the atmosphere of Saturn's moon, Titan. Methane absorption is not expected at the temperatures of main-sequence stars. This discovery helped to establish yet another spectral class even cooler than L dwarfs known as "T dwarfs" for which Gl 229B is the prototype.

Since 1995, when the first brown dwarf was confirmed by a Chilean astronomer named María Teresa Ruiz, hundreds have been identified. Brown dwarfs close to Earth include Epsilon Indi Ba and Bb, a pair of dwarfs gravitationally bound to a sunlike star, around 12 light-years from the Sun.

Theory

The standard mechanism for star birth is through the gravitational collapse of a cold interstellar cloud of gas and dust. As the cloud contracts it heats up from the release of gravitational potential energy. Early in the process the contracting gas quickly radiates away much of the energy, allowing the collapse to continue. Eventually, the central region becomes sufficiently dense to trap radiation. Consequently, the central temperature and density of the collapsed cloud increases dramatically with time, slowing the contraction, until the conditions are hot and dense enough for thermonuclear reactions to occur in the core of the protostar. For most stars, gas and radiation pressure generated by the thermonuclear fusion reactions within the core of the star will support it against any further gravitational contraction. Hydrostatic equilibrium is reached and the star will spend most of its lifetime fusing hydrogen into helium as a main-sequence star.

If, however, the mass of the protostar is less than about 0.08 solar mass, normal hydrogen thermonuclear fusion reactions will not ignite in the core. Gravitational contraction does not heat the small protostar very effectively, and before the temperature in the core can increase enough to trigger fusion, the density reaches the point where electrons become closely packed enough to create quantum electron degeneracy pressure. According to the brown dwarf interior models, typical conditions in the core for density, temperature and pressure are expected to be the following:

Further gravitational contraction is prevented and the result is a "failed star", or brown dwarf that simply cools off by radiating away its internal thermal energy.

Distinguishing high mass brown dwarfs from low mass stars

Lithium: Lithium is generally present in brown dwarfs and not in low-mass stars. Stars, which achieve the high temperature necessary for fusing hydrogen, rapidly deplete their lithium. This occurs by a collision of Lithium-7 and a proton producing two Helium-4 nuclei. The temperature necessary for this reaction is just below the temperature necessary for hydrogen fusion. Convection in low-mass stars ensures that lithium in the whole volume of the star is depleted. Therefore, the presence of the lithium line in a candidate brown dwarf's spectrum is a strong indicator that it is indeed substellar. The use of lithium to distinguish candidate brown dwarfs from low-mass stars is commonly referred to as the lithium test, and was pioneered by Rafael Rebolo and colleagues.

- However, lithium is also seen in very young stars, which have not yet had a chance to burn it off. Heavier stars like our sun can retain lithium in their outer atmospheres, which never get hot enough for lithium depletion, but those are distinguishable from brown dwarfs by their size.

- Contrariwise, brown dwarfs at the high end of their mass range can be hot enough to deplete their lithium when they are young. Dwarfs of mass greater than 65

can burn off their lithium by the time they are half a billion years old[Kulkarni], thus this test is not perfect.

can burn off their lithium by the time they are half a billion years old[Kulkarni], thus this test is not perfect.

Methane: Unlike stars, older brown dwarfs are sometimes cool enough that over very long periods of time their atmospheres can gather observable quantities of methane. Dwarfs confirmed in this fashion include Gliese 229B.

Luminosity: Main sequence stars cool, but eventually reach a minimum luminosity which they can sustain through steady fusion. This varies from star to star, but is generally at least 0.01% the luminosity of our Sun. Brown dwarfs cool and darken steadily over their lifetimes: sufficiently old brown dwarfs will be too faint to be detectable.

Iron rain as part of atmospheric convection processes is possible only with brown dwarfs, and not with small stars. The spectroscopy research into iron rain is still ongoing–and not all brown dwarfs will always have this atmospheric anomaly.

Distinguishing low mass brown dwarfs from high mass planets

A remarkable property of brown dwarfs is that they are all roughly the same radius as Jupiter. At the high end of their mass range (60–90 Jupiter masses), the volume of a brown dwarf is governed primarily by electron degeneracy pressure[2], as it is in white dwarfs; at the low end of the range (10 Jupiter masses), their volume is governed primarily by Coulomb pressure, as it is in planets. The net result is that the radii of brown dwarfs vary by only 10–15% over the range of possible masses. This can make distinguishing them from planets difficult.

In addition, many brown dwarfs undergo no fusion; those at the low end of the mass range (under 13 Jupiter masses) are never hot enough to fuse even deuterium, and even those at the high end of the mass range (over 60 Jupiter masses) cool quickly enough that they no longer undergo fusion after a period of time on the order of 10 million years. However, there are other ways to distinguish dwarfs from planets:

Density is a clear giveaway. Brown dwarfs are all about the same radius; so anything that size with over 10 Jupiter masses is unlikely to be a planet.

X-ray and infrared spectra are telltale signs. Some brown dwarfs emit X-rays; and all "warm" dwarfs continue to glow tellingly in the red and infrared spectra until they cool to planetlike temperatures (under 1000 K).

Gas giant planets have some of the characteristics of brown dwarfs. For example, Jupiter and Saturn are both made primarily of hydrogen and helium, like the Sun. Saturn is nearly as large as Jupiter, despite having only 30% the mass. Three of the giants in our solar system (Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune) emit more heat than they receive from the Sun. And all four giant planets have their own "planetary systems"—their moons. In addition, it has been found that both planets and brown dwarfs can have eccentric orbits.

Currently, the International Astronomical Union considers an object with a mass above the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium (currently calculated to be 13 Jupiter masses for objects of solar metallicity) to be a brown dwarf, whereas an object under that mass (and orbiting a star or stellar remnant) is considered a planet.[3]

Observations

Classification of brown dwarfs

Spectral class M

There are brown dwarfs with spectral of M6.5 or later. They are also called Late-M dwarfs.

Spectral class L

The defining characteristic of spectral class M, the coolest type in the long-standing classical stellar sequence, is an optical spectrum dominated by absorption bands of titanium(II) oxide (TiO) and vanadium(II) oxide (VO) molecules. However, GD 165B, the cool companion to the white dwarf GD 165 had none of the hallmark TiO features of M dwarfs. The subsequent identification of many field counterparts to GD 165B ultimately led Kirkpatrick and others to the definition of a new spectral class, the L dwarfs, defined in the red optical region not by weakening metal-oxide bands (TiO, VO), but strong metal hydride bands (FeH, CrH, MgH, CaH) and prominent alkali metal lines (Na I, K I, Cs I, Rb I). As of April 2005, over 400 L dwarfs have been identified (see link in references section below), most by wide-field surveys: the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS), the Deep Near Infrared Survey of the Southern Sky (DENIS), and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS).

Spectral class T

As GD 165B is the prototype of the L dwarfs, Gliese 229B is the prototype of a second new spectral class, the T dwarfs. Whereas near-infrared (NIR) spectra of L dwarfs show strong absorption bands of H2O and carbon monoxide (CO), the NIR spectrum of Gliese 229B is dominated by absorption bands from methane (CH4), features that were only found in the giant planets of the solar system and Titan. CH4, H2O, and molecular hydrogen (H2) collision-induced absorption (CIA) give Gliese 229B blue near-infrared colors. Its steeply sloped red optical spectrum also lacks the FeH and CrH bands that characterize L dwarfs and instead is influenced by exceptionally broad absorption features from the alkali metals Na and K. These differences led Kirkpatrick to propose the T spectral class for objects exhibiting H- and K-band CH4 absorption. As of April 2005, 58 T dwarfs are now known. NIR classification schemes for T dwarfs have recently been developed by Adam Burgasser and Tom Geballe. Theory suggests that L dwarfs are a mixture of very low-mass stars and sub-stellar objects (brown dwarfs), whereas the T dwarf class is composed entirely of brown dwarfs. Because of the absorption of sodium and potassium in the green part of the spectrum of T dwarfs, the actual appearance of T dwarfs to human visual perception is estimated to be not brown, but the color of magenta coal tar dye.[4][5]

Spectral class Y

Class Y dwarfs are expected to be much cooler than T-dwarfs. They have been modelled[6], though there is no well-defined spectral sequence yet with prototypes.

- Y: < 700 K, ultra-cool brown dwarfs (theoretical)

As of early 2009, the coolest known brown dwarfs have estimated effective temperatures between 500 and 600 K, and have been assigned the spectral class T9. Three examples are the brown dwarfs CFBDS J005910.90-011401.3, ULAS J133553.45+113005.2, and ULAS J003402.77−005206.7.[7] The spectra of these objects display absorption around 1.55 micrometers.[7] Delorme et al. has suggested that this feature is due to absorption from ammonia and that this should be taken as indicating the T-Y transition, making these objects of type Y0.[7][8] However, the feature is difficult to distinguish from absorption by water and methane,[7] and other authors have stated that the assignment of class Y0 is premature.[9]

In April 2010, two newly discovered ultracool brown subdwarfs (UGPS 0722-05 and SDWFS 1433+35[10]) were proposed as prototypes for spectral class Y0.

Spectral and atmospheric properties of brown dwarfs

The majority of flux emitted by L and T dwarfs is in the 1 to 2.5 micrometre near-infrared range. Low and decreasing temperatures through the late M, L, and T dwarf sequence result in a rich near-infrared spectrum containing a wide variety of features, from relatively narrow lines of neutral atomic species to broad molecular bands, all of which have different dependencies on temperature, gravity, and metallicity. Furthermore, these low temperature conditions favor condensation out of the gas state and the formation of grains.

Typical atmospheres of known brown dwarfs range in temperature from 2200 down to 750 K.[4] Compared to stars, which warm themselves with steady internal fusion, brown dwarfs cool quickly over time; more massive dwarfs cool more slowly than less massive ones.

Observational techniques

Coronagraphs have recently been used to detect faint objects orbiting bright visible stars, including Gliese 229B.

Sensitive telescopes equipped with charge-coupled devices (CCDs) have been used to search distant star clusters for faint objects, including Teide 1.

Wide-field searches have identified individual faint objects, such as Kelu-1 (30 ly away)

Milestones

- 1995: First brown dwarf verified. Teide 1, an M8 object in the Pleiades cluster, is picked out with a CCD in the Spanish Observatory of Roque de los Muchachos of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias.

- First methane brown dwarf verified. Gliese 229B is discovered orbiting red dwarf Gliese 229A (20 ly away) using an adaptive optics coronagraph to sharpen images from the 60 inch (1.5 m) reflecting telescope at Palomar Observatory on Southern California's Mt. Palomar; followup infrared spectroscopy made with their 200 inch (5 m) Hale telescope shows an abundance of methane.

- 1998: First X-ray-emitting brown dwarf found. Cha Halpha 1, an M8 object in the Chamaeleon I dark cloud, is determined to be an X-ray source, similar to convective late-type stars.

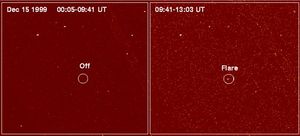

- December 15, 1999: First X-ray flare detected from a brown dwarf. A team at the University of California monitoring LP 944-20 (60 Jupiter masses, 16 ly away) via the Chandra X-ray Observatory, catches a 2-hour flare.

- 27 July 2000: First radio emission (in flare and quiescence) detected from a brown dwarf. A team of students at the Very Large Array reported their observations of LP 944-20 in the 15 March 2001 issue of the journal Nature.

Brown dwarf as an X-ray source

X-ray flares detected from brown dwarfs since late 1999 suggest changing magnetic fields within them, similar to those in very low-mass stars.

With no strong central nuclear energy source, the interior of a brown dwarf is in a rapid boiling, or convective state. When combined with the rapid rotation that most brown dwarfs exhibit, convection sets up conditions for the development of a strong, tangled magnetic field near the surface. The flare observed by Chandra from LP 944-20 could have its origin in the turbulent magnetized hot material beneath the brown dwarf's surface. A sub-surface flare could conduct heat to the atmosphere, allowing electric currents to flow and produce an X-ray flare, like a stroke of lightning. The absence of X-rays from LP 944-20 during the non flaring period is also a significant result. It sets the lowest observational limit on steady X-ray power produced by a brown dwarf star, and shows that coronas cease to exist as the surface temperature of a brown dwarf cools below about 2500°C and becomes electrically neutral.

Using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, scientists have detected X-rays from a low mass brown dwarf in a multiple star system.[11] This is the first time that a brown dwarf this close to its parent star(s) (Sun-like stars TWA 5A) has been resolved in X-rays.[11] "Our Chandra data show that the X-rays originate from the brown dwarf's coronal plasma which is some 3 million degrees Celsius", said Yohko Tsuboi of Chuo University in Tokyo.[11] "This brown dwarf is as bright as the Sun today in X-ray light, while it is fifty times less massive than the Sun", said Tsuboi.[11] "This observation, thus, raises the possibility that even massive planets might emit X-rays by themselves during their youth!"[11]

Recent developments

Recent observations of known brown dwarf candidates have revealed a pattern of brightening and dimming of infrared emissions that suggests relatively cool, opaque cloud patterns obscuring a hot interior that is stirred by extreme winds. The weather on such bodies is thought to be extremely violent, comparable to but far exceeding Jupiter's famous storms.

The brown dwarf Cha 110913-773444, located 500 light years away in the constellation Chamaeleon, may be in the process of forming a mini solar system. Astronomers from Pennsylvania State University have detected what they believe to be a disk of gas and dust similar to the one hypothesized to have formed our own solar system. Cha 110913-773444 is the smallest brown dwarf found to date (8 Jupiter masses), and if it formed a solar system, it would be the smallest known object to have one. Their findings were published in the Dec. 10 issue of the Astrophysical Journal[12][13]

NASA's WISE mission is expected to detect many additional brown dwarfs, some of which are expected to be closer to the Earth than Proxima Centauri.[14] [15]

Notable brown dwarfs

- 2M1207: first brown dwarf discovered with a planetary mass in orbit about it

- WD 0137-349 B: first confirmed brown dwarf to have survived the primary's red giant phase.[16]

- It has also been predicted, by some astronomers, that the Sun may be orbited by an as yet unobserved brown dwarf (sometimes referred to as Nemesis) which interacts with the Oort cloud (and may have helped shape the position of the dwarf planets) [17].

| Brown Dwarfs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Brown Dwarf Name | Spectral Type | RA/Dec | Constellation | Notes |

| First discovered | Gliese 229 B | T6.5 | 06h10m34.62s -21°51'52.1" | Lepus | Discovered 1994 |

| First directly imaged | Gliese 229 B | T6.5 | 06h10m34.62s -21°51'52.1" | Lepus | Discovered 1994 |

| First verified | Teide 1 | M8 | 3h47m18.0s +24°22'31" | Taurus | 1995 |

| First with planemo | 2MASSW J1207334-393254 | M8 | 12h07m33.47s -39°32'54.0" | Centaurus | |

| First with a dust disk | |||||

| First with bipolar outflow | |||||

| First field type (solitary) | Teide 1 | M8 | 3h47m18.0s +24°22'31" | Taurus | 1995 |

| First as a companion to a normal star | Gliese 229 B | T6.5 | 06h10m34.62s -21°51'52.1" | Lepus | 1995 |

| First in a multi-star system | |||||

| First binary brown dwarf | Epsilon Indi Ba, Bb [2] | T1 + T6 | Indus | Distance: 3.626pc | |

| First trinary brown dwarf | DENIS-P J020529.0-115925 A/B/C | L5, L8 and T0 | 02h05m29.40s -11°59'29.7" | Cetus | Delfosse et al. 1997, mentions |

| First halo brown dwarf | 2MASS J05325346+8246465 | sdL7 | 05h32m53.46s +82°46'46.5" | Gemini | Adam J. Burgasser, et al. 2003 |

| First Late-M spectra | Teide 1 | M8 | 3h47m18.0s +24°22'31" | Taurus | 1995 |

| First L spectra | |||||

| First T spectra | Gliese 229 B | T6.5 | 06h10m34.62s -21°51'52.1" | Lepus | 1995 |

| Latest T spectrum | ULAS J0034-00 | T9 [18] | Cetus | 2007 | |

| First Y spectrum | CFBDS0059 - pending[8] This is also classified as a T9 dwarf, due to its close resemblance to other T dwarfs [18] | ~Y0 | 2008 | ||

| First X-ray-emitting | Cha Halpha 1 | M8 | Chamaeleon | 1998 | |

| First X-ray flare | LP 944-20 | M9V | 03h39m35.22s -35°25'44.1" | Fornax | 1999 |

| First radio emission (in flare and quiescence) | LP 944-20 | M9V | 03h39m35.22s -35°25'44.1" | Fornax | 2000 |

| Brown Dwarfs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Brown Dwarf Name | Spectral Type | RA/Dec | Constellation | Notes |

| Oldest | |||||

| Youngest | |||||

| Heaviest | |||||

| Metal-rich | |||||

| Metal-poor | 2MASS J05325346+8246465 | sdL7 | 05h32m53.46s +82°46'46.5" | Gemini | distance is ~10–30pc, metallicity is 0.1–0.01ZSol |

| Lightest | |||||

| Largest | |||||

| Smallest | |||||

| Furthest to primary star | |||||

| Nearest to primary star | |||||

| Furthest | |||||

| Nearest | Epsilon Indi Ba, Bb [3] | T1 + T6 | Indus | Distance: 3.626pc | |

| Nearest binary | Epsilon Indi Ba, Bb [4] | T1 + T6 | Indus | Distance: 3.626pc | |

| Brightest | |||||

| Dimmest | 2MASS J09393548-2448279[19] | ||||

| Hottest | |||||

| Coolest | ULAS J133553.45+113005.2 | T9/Y0 | Temperature 500–550 K;[7] distance 26-40 ly; 15–31 times the mass of Jupiter; reported June 2008; found in data from the UKIRT Infrared Deep Sky Survey (UKIDSS) Large Area Survey (LAS)[20] | ||

| Most dense | COROT-3b [21] | Its radius is too small for it to be a super-planet. If it is a star, it would be among the smallest ever detected. Follow-up observations from the ground have pinned it at 20 Jupiter masses. This makes it twice as dense as the metal platinum. | |||

| Least dense | |||||

See also

- Dark matter

- Brown-dwarf desert

- Stellar objects

- Blue dwarf

- Orange dwarf

- Red dwarf

- Yellow dwarf

Substellar objects

- Extrasolar planet

- Sub-brown dwarf

References

- ↑ Boss, Alan (2001-04-03). "Are They Planets or What?". Carnegie Institution of Washington. http://www.carnegieinstitution.org/News4-3,2001.html. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ "Planetesimals to Brown Dwarfs: What is a Planet?". 2006-08-20. http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0608417. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ↑ "Working Group on Extrasolar Planets: Definition of a "Planet"". IAU position statement. 2003-02-28. http://www.dtm.ciw.edu/boss/definition.html. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Burrows et al. The theory of brown dwarfs and extrasolar giant planets. Reviews of Modern Physics 2001; 73: 719-65 doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.73.719

- ↑ "An Artist's View of Brown Dwarf Types" Dr. Robert Hurt of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center

- ↑ Y-Spectral class for Ultra-Cool Dwarfs, N.R.Deacon and N.C.Hambly, 2006

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 The Physical Properties of Four ~600 K T Dwarfs, S. K. Leggett et al., The Astrophysical Journal 695, #2 (April 2009), pp. 1517–1526, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/695/2/1517, Bibcode: 2009ApJ...695.1517L.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 CFBDS J005910.90-011401.3: reaching the T-Y brown dwarf transition?, P. Delorme et al., Astronomy and Astrophysics 482, #3 (May 2008), pp. 961–971, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20079317, Bibcode: 2008A&A...482..961D.

- ↑ Exploring the substellar temperature regime down to ~550K, Ben Burningham et al., Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 391, #1 (November 2008), pp. 320–333, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13885.x, Bibcode: 2008MNRAS.391..320B; see the abstract.

- ↑ P. Eisenhart et al.. "Ultracool Field Brown Dwarf Candidates Selected at 4.5 microns". Cornell University Library. http://arxiv.org/abs/1004.1436. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 "X-rays from a Brown Dwarf's Corona". April 14, 2003. http://www.williams.edu/Astronomy/jay/chapter18_etu6.html.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Letters

- ↑ Wright, Ned (2003-02-26). "WISE and Brown Dwarfs". http://www.astro.ucla.edu/~wright/WISE/bd.html. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- ↑ Gilster, Paul (2009-11-13). "WISE: Brown Dwarf Hunter Extraordinaire". Centauri Dreams: The News Forum of the Tau Zero Foundation. Tau Zero Foundation. http://www.centauri-dreams.org/?p=10216. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- ↑ Maxted P. F. L. et al. (2006). "Survival of a brown dwarf after engulfment by a red giant star". Nature 442 (7102): 543. doi:10.1038/nature04987. PMID 16885979.

- ↑ Daniel P. Whitmire, Albert A. Jackson. 1984, Nature, 308, 713. Also Richard A. Muller. 2004, Geological Society of America Special Paper 356, 659-665

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Exploring the substellar temperature regime down to ~550K, Ben Burningham et al. 2008

- ↑ NASA/JPL (2008-12-10). "Astronomers Find the Two Dimmest Stellar Bulbs". Press release. http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.cfm?release=2008-232. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ Exploring the substellar temperature regime down to ~550K, Ben Burningham et al., Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 391, #1 (November 2008), pp. 320–333, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13885.x, Bibcode: 2008MNRAS.391..320B. The arXiv e-print of this paper, arXiv:0806.0067, was first submitted June 2, 2008.

- ↑ ESA Portal - Exoplanet hunt update

External links

History

- S. S. Kumar, Low-Luminosity Stars. Gordon and Breach, London, 1969—an early overview paper on brown dwarfs

- The Columbia Encyclopedia

Details

- A current list of L and T dwarfs

- A geological definition of brown dwarfs, contrasted with stars and planets (via Berkeley)

- Neill Reid's pages at the Space Telescope Science Institute:

- On spectral analysis of M dwarfs, L dwarfs, and T dwarfs

- Temperature and mass characteristics of low-temperature dwarfs

- First X-ray from brown dwarf observed, Spaceref.com, 2000

- Brown Dwarfs and ultracool dwarfs (late-M, L, T) - D. Montes, UCM

- Wild Weather: Iron Rain on Failed Stars - scientists are investigating astonishing weather patterns on brown dwarfs, Space.com, 2006

- NASA Brown dwarf detectives - Detailed information in a simplified sense.

- Brown Dwarfs - Website with general information about brown dwarfs (has many detailed and colorful artist's impressions).

Stars

- Cha Halpha 1 stats and history

- A census of observed brown dwarfs (not all confirmed), ca 1998

- Epsilon Indi Ba and Bb, a pair of brown dwarfs 12 ly away

- Luhman et al., Discovery of a Planetary-Mass Brown Dwarf with a Circumstellar Disk

- Discovery Narrows the Gap Between Planets and Brown Dwarfs, 2007

- Y-Spectral class for Ultra-Cool Dwarfs, N.R.Deacon and N.C.Hambly, 2006

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||